Monthly Archives: May 2018

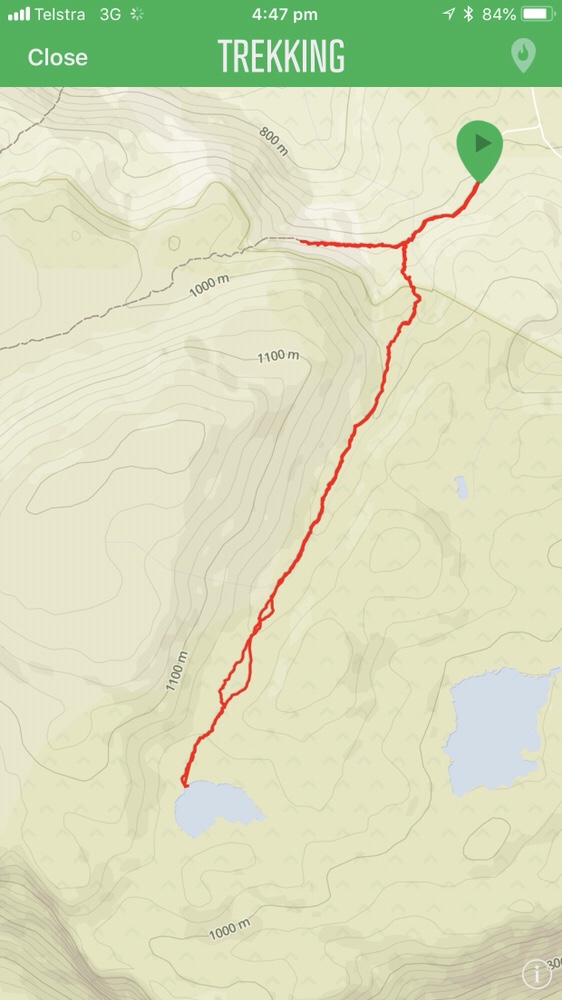

Lake McCoy

It was an early start for me. We set the alarm for 6:30. I looked out the window at the far end of the corridor to see dawn breaking through a twisted dark cloud. I braved the front door, oooh, cold. I went back inside and upgraded the equipment I’d planned to take on today’s walk.

I met everyone else at LINC in High Street, loaded up my pack and boots into the boot of Trevor’s car. I travelled with Elaine, Trevor and Julie. While the six others came in other vehicles. It’s 125 km to the point on Maggs road that is the starting point for the walk. The day simply became more beautiful, dissipating my worries about a too cold day. The weather could not have been kinder or more enchanting. The rich blue sky providing a striking clarity to landscape.

The start of the walk does not look all that auspicious, piles of forestry debris gathered into numerous piles in readiness for an autumn ignition. The track sets up through scrub, the trees and shrubs almost and in fact often do obscure the way. Trees have belligerently decided to land the length of the track. This obliterates the route and provides a slippery obstacle to clamber over. Pink, yellow, orange and white ( faded coloured plastic ribbons) hang off tree branches and stumps. The route these impromptu signposts provide should be thought of in the many not the few. As previous walkers got lost, they started tying on plastic ribbons, and so producing a bewilderingly complex labyrinth in what is already a nearly opaque track. It’s slippery, uneven and as we ascended given to sudden collapse. The track for a substantial part of the way goes over sphagnum moss. And it’s deep, my boots springing and sinking in the pale green moss, it’s like walking on a too soft mattress but the simile collapses as suddenly the right or left leg drops through into the wet never never World of sodden peat beneath. My boots were very damp by the end of the walk.

The track provides a steady climb with occasional pauses to clamber, slip, fall over, land spreadeagled on the moss, or wonder where the track might be. We began with a detour. After we crossed a creek, we missed correct turn off to the right and instead carried on straight ahead. Elaine raised the alarm. We were walking west rather than the correct south. Neville located the right track. The storms and rain have sent an enormous amount of debris, twigs, branches, tree limbs and trees, and rocks over the track. It’s not easy. This is not a walk I would ever contemplate doing alone. The other Ramblers are highly experienced bush walkers and thought flummoxed at times, soon sorted out the right direction. The path was never more than 15 cm wide.

The track enters a narrow valley with a central strip of pools, and sphagnum, of scoparia sprawled over the ground, it’s red spikes looking listless, lacking their carnivorous predilections, and Bauera, for once benignly hovering against woolybutt, snow gums and pencil pines.

We entered an arbor, of luxurious moss, soft and spongy, and shaded by healthy pencil pines. A small tarn glowed orange and red beneath the pines, even at noon, the time of the most unkind light. I took a few photographs and as quickly as that I thought, where are everybody. The twisting track, the scrub and dips, meant it was very important to keep alert. It would be too easy to get lost here. Occasionally I’d hear the others call out ‘ Bruce’ . I answered and caught up.

Lake McCoy, is beautiful. It’s most striking feature for me was it’s stillness. What an evanescent virtue? Many pencil pines and woolybutts, crowd most of the lake shore, reflections perfect in the water. Water plants hover just beneath the surface, their cream leaves dimpling the water. The western edge of the tiers is visible behind the pencil pines, it’s abrupt cliffs beneath a flat topped Mesa.

We all enjoyed our lunches in the warm sunshine, took Photos and squelched around in the streams, pools and moss. Very enjoyable. However time was getting on, so we packed up, Trevor put on his back pack, reminding us all there was still more walking to do to get back in daylight.

We walked back to the cars. The track was substantially easier to follow on the way back. It was important to ignore many of the ribbons. Neville lead the way, setting up a quick pass despite the rough, narrow, winding track, and only taking notice of the correctly placed markers. It’s a gift!

We crossed the creek, and it was only a short step back to cars parked at the coup. Lots of the mothers needed to get back to Launceston for Mother’s Day functions so it was a no nonsense descent through the scrub.

It’s been a terrific day, great company, challenging walking and navigation, warm sunshine, and a wonderful natural experience.

HTLV1 another piece in the puzzle

On Friday afternoon, all the doctors who work at Central Australian Health Service (CAHS) and happen to be in Alice Springs, meet up at 2 o’clock in the conference room in the Peter Sitzler building. It’s a chance to discuss cases, developments, and in recent times, talk with a specialist about an aspect of remote medicine.

All of us living in Alice Springs and Central Australia are very aware of the serious health problems of Indigenous people. On the roads or near a remote township, it’s common to look up at the sound of an aircraft engine and see a retrieval plane with their characteristic red belly. Anyone working in a small town in the outback will have seen the skin diseases, effects of poor nutrition, and disabilities of the many people who live there. As health professionals in the Centre, we treat people with the most severe forms seen in Australia, of diabetes, kidney and cardiac disease. The health crisis is no secret to anyone.

The causes of this burden of disease, premature death, and disability are multi factorial and therefore should be approached at multiple levels to have any chance of success. Putting as it were, all your apples in one basket is not going to work. Targeting all the money and your efforts in only supplying doctors and nurses cannot and is not, the only strategy. It fits with older ideas of targeting clinical disease but doesn’t it make more sense to have a global approach, a preventative emphasis. There is already an aggressive territory wide program of immunisation with uptake rates higher than many affluent regions in white Australia. There is also a strong emphasis on antenatal care, improving the intrauterine environment for the next generation and protecting the well being of all the mothers to be.

Nutrition that’s inexpensive and healthy, real home safety and security, clean, reliable water, and freedom from the consequences of alcohol (FASD : Foetal Alcohol syndrome) and drug abuse, are all going to have to be tackled to achieve the level of health we demand for our patients. However, these issues are out of our hands, and very largely in the legislative arena, needing to be backed up by targeted programs with clear, and long term goals utterly divorced from the usual three year cycle of funding.

But for all this, the science of remote medicine is in its infancy. It’s hard making definitive statements about what should and what should not be done without the science to back up decisions. Until you have solid evidence, it’s all opinion not fact. I cannot begin to imagine making sense of infectious diseases without knowing about bacteria and viruses, but this was the situation for doctors in most of the nineteenth century and for all of human history before then. How could surgery be contemplated or completed with any safety without understanding and applying principles of antisepsis and the science of anaesthesia? Done in desperation, it was so savage and so dangerous, that it gave lasting horror to any surviving patient and surgeon both. The more reliable science we have about health, and in particular about here in Central Australia, the better.

Addressing the social determinants of disease is essential and cannot be ignored but none the less, the science of disease has to be up to scratch too. At present we apply our clinical knowledge on Indigenous peoples, but our expertise was gained in other populations that rarely includes such peoples. The science we use to make clinical decisions about the best medical care has been largely developed by studying disease in other populations, and often in other countries. The necessary studies now being done on heart failure and diabetes, to name two common morbidities, are in their infancy. Major institutes including the Menzies foundation and Baker IDI are doing ground breaking research projects, which are beginning to clarify the ways we need to treat. It’s known that certain cardiac medications work best in black Americans and hardly at all in White Americans, and could it be that this is the case here too? Maybe there are some drugs that will only work in Australian Aboriginal people? There are so many questions which need to asked and answered.

However, one major piece of the puzzle of Indigenous ill heath is coming to light. A virus called HTLV1 may prove responsible for many of the poor outcomes we see amongst our patients as well as contributing to progressive neurological and lung disease. This virus is not a factor anyone needs to consider when treating middle class people in Sydney or Melbourne but here in Central Australia, understanding this virus and it’s effects may prove crucial to getting on top of Indigenous health. It’s early days but even now, there are tantalising clues to how important it could be. Okay, I’ve mentioned HTLV 1, now it’s time to be properly introduced and like the most interesting person at a party, it’s well worth getting to know.

HTLV1 stands for Human T Cell lymphotrophic Virus and its a cousin of HIV ( Human Immunodeficency virus) and just like it’s better known relation, it comes from monkeys as well as apes. Unlike HIV it is not a new arrival in a human population. It’s been in Northern Australia for at least ten thousand years, it’s origins are in Melanesia. Other strains of HTLV1 occur in Japan, South America and Africa. They cause similar diseases in all these places but the percentages wildly vary, causing mostly neurological problems in South America, T cell Leukemia in Japan, and Lung disease here in Central Australia.

This virus is spread from mothers to their babies when breast feeding, and is sexually spread. This accounts for the steady increase in the percentage of people as life goes by. Up to 50% of people in some parts of Central Australia have this virus. It seems that for the majority of people with this infection they are unaffected but a over a third of infected people have significant risk of complications that can disable or kill them.

How does it do this? And more importantly why does it do this? HTLV1 infects CCR4 cells, a type of T cell or defence cell. I won’t bother with the meaning of the acronym but suffice it to say, the virus infects these special cells which are a small but essential” part of the immune system, and upcodes itself into the DNA of the cell. It hides incredibly successfully, so well that it cannot be eradicated. It then drives the replication of these cells, their numbers get greater and thereby the numbers of the hidden virus increase too. Some people due to their genetics have the capacity to control the level of replication and these individuals suffer little from the infection. However those who cannot, can have high pro- viral loads. The term “ pro viral” refers to the pro or hidden form of the virus imbedded in the DNA. Those individuals with high levels of the pro- virus are the people who develop the serious health problems mentioned above.

When there are vast numbers of CCR4 cells, there is too much of the chemical they make. This chemical is called gamma interferon. Small amounts in the right place, delivered in the right time can help with fighting infection. Too much of this agent damages organs and tissues, including the spinal cord, and eyes in particular. And maybe other organs, we don’t know. The investment the body has been forced to make means less of the other defensive cells, less numbers, less diversity so the capacity to actually fight infection efficiently is hijacked. This means troublesome if not lethal infections; including tuberculosis, strongyloides ( a parasitic infection of gut and lung), bronchiectasis ( a damaging process that destroys the airways and increases the risk of and the severity of lung infections) and the most severe forms of scabies. If the number of CCR4 cells gets totally out of hand, this can lead to malignancy, T cell leukaemia. This is how the HTLV1 virus was first discovered in Japanese patients.

This propensity to trigger and worsen infection as well as produce tissue damage in its own right via its zombified T cells, CCR4, could be a factor in other diseases including Kidney disease. There is so much to find out. There are treatments for this infection but it’s complex and not without risk. Exciting, new agents seem to be effective but are terribly expensive and only just leaving laboratories to be studied in the real world. The costs of such treatments will need to be weighed up against the good they can do.

So, remote medicine is throwing up all sorts of challenges and it needs to tackled in all sorts of ways, including; innovative social policies, sustained government interest and support, improving antenatal care, continuing to improve the rates of immunisation, supplying and training interested, passionate doctors, nurses and health workers and lastly, investment in basic science to elucidate the mechanisms of disease relevant to this local Indigenous population.

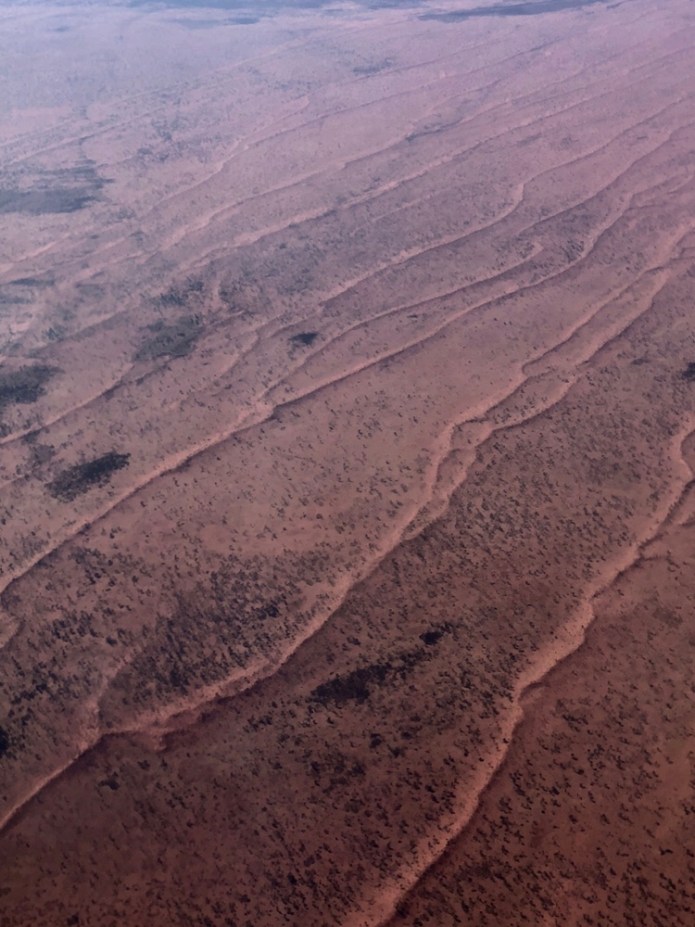

Western Desert low altitude Photos

The west in the Central Australia refers to the country beyond and surrounding the West McDonnell ranges and extending as far as the West Australian border. I flew west from Alice Springs to Nyirripi, northwest of Yuendemu. I looked out the window and watched the ground beneath me. First there are mountains, some grouped in clusters some as part of long ranges, they all rise abruptly from the desert and are almost bare of vegetation. It was early morning and the shadows cast on the western slopes makes that part of the landscapes invisible but the obliquely of the light highlights the jagged ridge lines. In the valleys between the high ground are sparse acacias and gum trees, they all rely on the rare flows of water down these mountainsides to survive.  The mountains and hills give way to swathes of red sand, rich in iron, a memory of the ancient sediments of great seas that covered this land. A time so lost in deep time, that nothing but insects crawled on its beaches, and fish with armour plates swam in the water and trilobites scurried on the sea floor. Now, dunes extend for hundreds of kilometres laid in long parallel lines. Yet, in some places this pattern is broken, the dunes interweave as if engaged in a timeless conversation leaning against each other.

The mountains and hills give way to swathes of red sand, rich in iron, a memory of the ancient sediments of great seas that covered this land. A time so lost in deep time, that nothing but insects crawled on its beaches, and fish with armour plates swam in the water and trilobites scurried on the sea floor. Now, dunes extend for hundreds of kilometres laid in long parallel lines. Yet, in some places this pattern is broken, the dunes interweave as if engaged in a timeless conversation leaning against each other.

There are more echoes of the seas, salt leached out of the earth by summers evanescent lakes are left behind by fierce evaporation.They can form simple circles, dead spotty soakages and in other places, weirdly tentacled ghosts haunting the earth.

There are more echoes of the seas, salt leached out of the earth by summers evanescent lakes are left behind by fierce evaporation.They can form simple circles, dead spotty soakages and in other places, weirdly tentacled ghosts haunting the earth.

There is an incredible diversity in the topography of the desert. This mountain range plows into the desert, leaving a bow wave of green spreading over the sand.

There is an incredible diversity in the topography of the desert. This mountain range plows into the desert, leaving a bow wave of green spreading over the sand.

Most of the roads are glorified tracks, some are of stone and gibber, some are rutted, punished clay and others yellow sand with sand pits and washes filling the deeper corrugations. They cross rivers, gorges, passes and all the empty miles between the remote settlements of the outback.These tracks and highways, are as necessary as water and as dangerous; tourists cars get flipped by deep sand or when young men play chicken on them and lose.

Every aspect of the desert must be treated with respect and caution, it’s beauty, it’s variety is amazing but in its immensity are the dangers of isolation, heat, thirst and fire. This place suffers no sentimentality, possesses no cruelty but nor has it any love for us that will protect us from folly or the perils of ill luck.