I’m onboard a RFDS turboprop as the door is being closed, and we are about to fly out of Alexandria Station. We will be flying an hour, about 300km back to Elliott. It’s a cool, clear day with a beautiful yellow light bathing and illuminating the station sheds and grassland. A flock of galahs is munching seed about twenty meters from the plane, with only the occasional look up to check how the rest of the world proceeds.

Alexandrina is the third cattle station we have visited on this tour. Every month, Tony ( a nurse usually based at Elliott) goes with the available doctor to three or more cattle stations to see the staff who live there. They are mostly young people who work as jackaroos, jillaroos, bore runners, mechanics, managers. There are some older folk as well. There are are a few children as well, who will be growing up on the station. When they are old enough they will be participating in School of the air. Until then it’s all fun.

The stations are vast affairs. The first one we visited is called Anthony’s Lagoon. It is about forty minutes flight time from Elliott, in the heart of the Barkly. We saw two people from that station but a nearby station called Walhollow sent across about eight people; so it turned out to be a busy afternoon. I have to record my notes on a word file as our normal software system we use at the clinic, is not available due to software and internet issues. It means I will spend the afternoon of my return transcribing it and copying it into PICUS.

The stations are trim, neat affairs with grassy lawns sporting cane toads desultorily hopping and the occasional King Brown snake slithering around a tree. It pays to use a torch at night as it would not be prudent to mistakenly stand on one, well either actually. Cane toads have recently arrived in the Barkly, travelling down the rivers and lagoons in the wet season. Even sea snakes have been washed here, about five hundred kilometres from the coast in gulf country such is the turbulence and abundance of water, thee can be seen swimming in the huge rivers. The buildings are steel clad, with comfortable interiors and basic but comfortable furniture and bedding. The verandas have chairs to sit and enjoy the evening chill and stretch out the legs. There is a mess hall, with a cooked breakfast at 5:30 am, lunch at noon and dinner at 7 pm. The standard of cooking varies with last nights meal of corn beef and vegetables the stand out. The station staff, sit at the tables, swapping stories about their days. They spend the day moving and managing the cattle, usually on horseback. Horsemanship is a very valued aspect of Barkly Culture.

Tomorrow the Brunett Races and Campdraft will be held about twenty-five kilometres from Brunett Station. Many of the local station staff and locals, will go to see the events and many will participate. Racing is a keen affair, it’s only local horses that can be entered in the events. The festival goes on for three days. There is bush poetry, music but the highlight is the Campdraft competition. Jodie, the receptionist explained what she will be doing when she competes. A fence encloses an area of two hundred square meters. In the square are a dozen steer. The competitor is on a horse, and the aim is to cut out one selected cow, move it into the centre, get it to turn two or three times. Now all this is done using the horse to manoeuvre the bigger animal. Then lead it out through a gate and then back in. The “gate” are two white hats in the enclosure. In real life, on a station, the skills and speed of this sort of activity means the safer movement of stock. The competitor who does it with the most style and speed wins. There is a womens and mens competition but again in the real world of station work, teams of station hands all work together. Some teams of a dozen or more, can be all female. The staff of whichever gender are expected to do the same work. In the evening, the girls are just as dirty and dishevelled from working as the fellows. Frequently, the staff are on camp. These camps can last weeks, working cattle over long distances to fresh bores and feed, while each night is spent sleeping under the stars.

Some of the young people are locals who were born here, some are long term visitors from Europe or the UK. From the dinner table, you can hear German, upper crust English accents and the drawl of NSW rural Strine. Its definitely an eclectic mix. There are some Aborigines but really, very few, and usually born on the station and as they have never left, never having experienced tribal life in a remote community.

The medicine is typical white fella medicine, contraception, smoking, and trauma mostly. There is none of the diabetes and kidney disease rampant in any Aboriginal community.

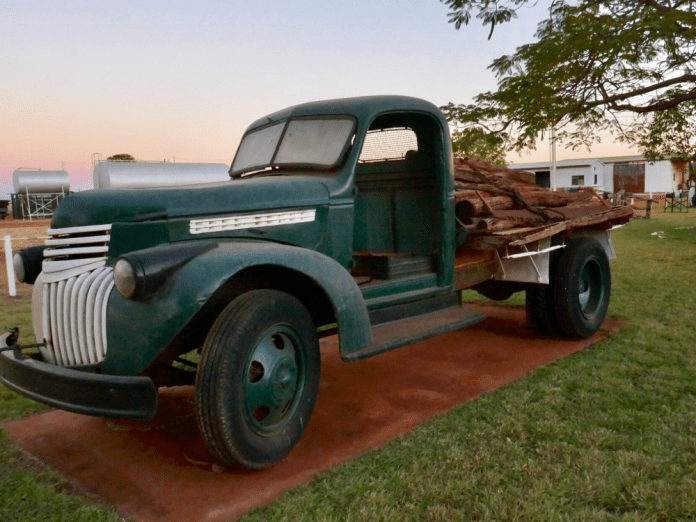

You may recall the photos I sent of Marlinja. Marlinja consists of a pleasant Aboriginal community, on land that was returned from the vast Newcastle Waters Station in the seventies: the station itself and between the two the ghost town of the original Marlinja. Here we parked the car, and walked through the old buildings. There is the abandoned Jones Hotel, the general store, and the petrol station with its old fashioned bowser. Marlinja was a thriving community, and the shops operating in the the locals lifetime. When there were poorer roads and few vehicles, it took a whole day to get to Elliott which is thirty kilometres away, it made sense to have amenities close by. Now food and supplies are flown in directly to the station. The famous Marrinjah ( Way stock route that enable stock to be moved from WA to Queensland brought huge mobs of drovers into the Jones Hotel for beer, shower and a comfortable bed. This stock route was also called the Death Way, as it went through desert, jungle, crossed lagoons and often flooded rovers, with snakes, crocodiles, all together a challenging journey for men and beasts. There is a very good book written about this which I will try to obtain if not in Tennant Creek, then on Booktopia.

When I look up from my writing, I can look across the wing and see down onto the Barkly, vast mottled and hazy regions of green in the now desiccated lagoons and desperately hugging the few waterholes still remaining. The rest is a brown flat land scarred by the sinuous paths of now dead rivers and the long, straight dirt roads connect bores and stations.

By the way, a bore runner is a person who drives from bore to bore checking they are working. Some times they are diesel mechanics but generally, they are people who love isolation and quiet.