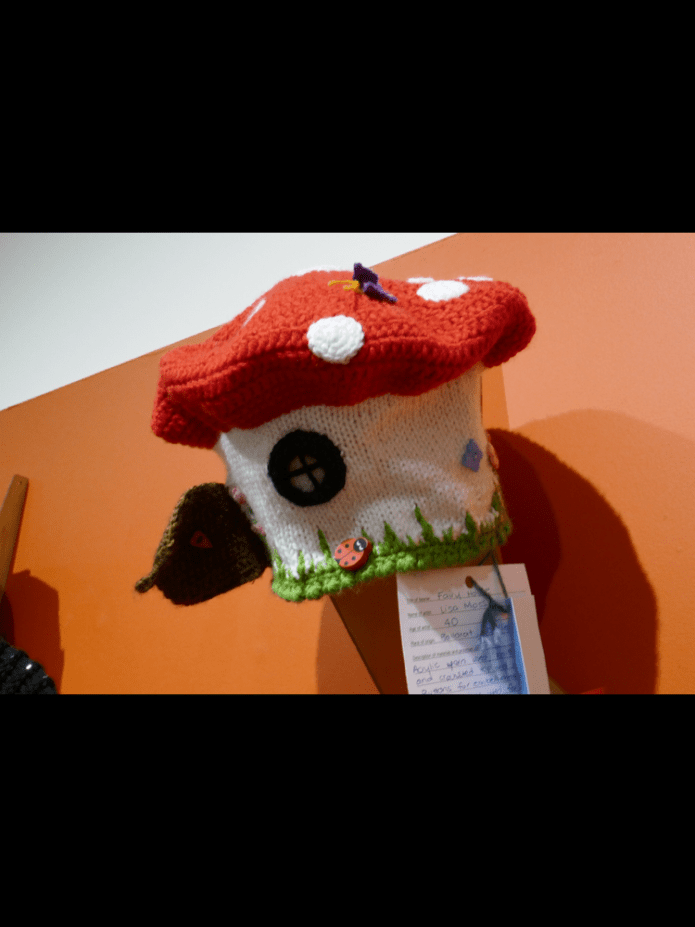

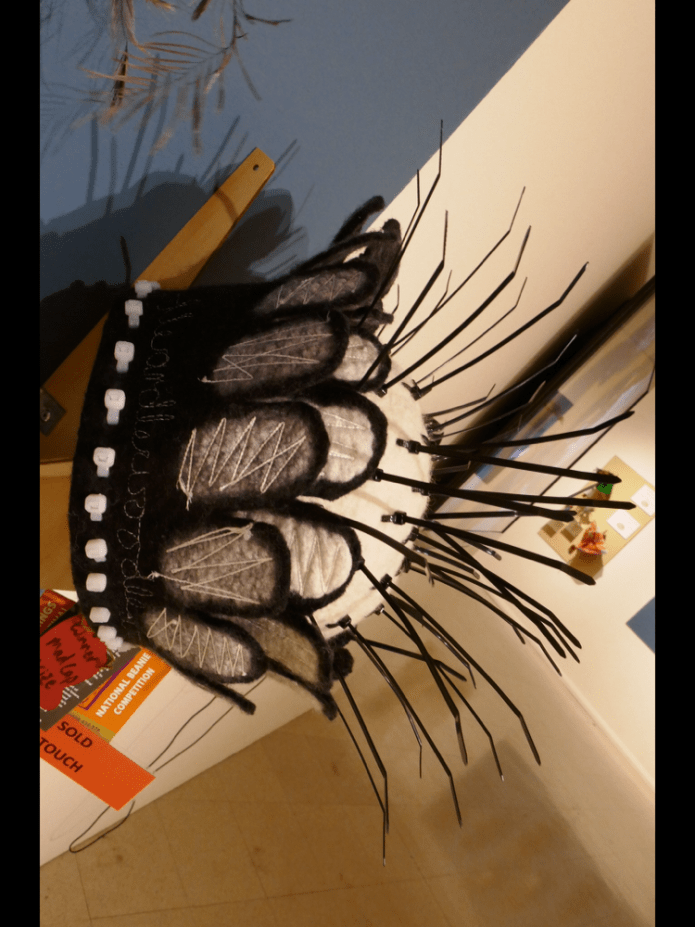

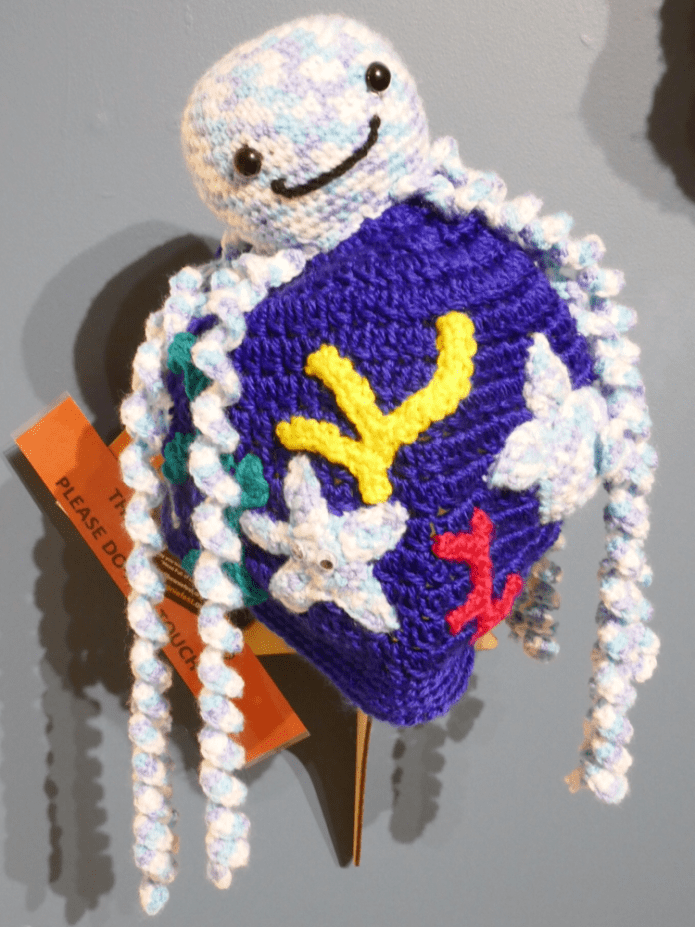

This annual event that lasts for four days is the biggest fund raiser for social welfare in Alice Springs. It began twenty one years ago showcasing the knitting of beanies, scarves, hats and tea cosies. There is a competition in the main hall at Araluen with some very spectacular beanies. There is a De Who character called the Ood, there are wildflowers, there are birds, there was area cosy which was an entire homestead! There were lots of people enjoying the works. Some are made locally by Aboriginal ladies > men and there are others made interstate by keen knitters. There are some very creative people aren’t there? We then visited the Beanie market and bought some beanies for the family.

Monthly Archives: June 2017

Central Australia Road trip 6 The Barkly Run

I’m onboard a RFDS turboprop as the door is being closed, and we are about to fly out of Alexandria Station. We will be flying an hour, about 300km back to Elliott. It’s a cool, clear day with a beautiful yellow light bathing and illuminating the station sheds and grassland. A flock of galahs is munching seed about twenty meters from the plane, with only the occasional look up to check how the rest of the world proceeds.

Alexandrina is the third cattle station we have visited on this tour. Every month, Tony ( a nurse usually based at Elliott) goes with the available doctor to three or more cattle stations to see the staff who live there. They are mostly young people who work as jackaroos, jillaroos, bore runners, mechanics, managers. There are some older folk as well. There are are a few children as well, who will be growing up on the station. When they are old enough they will be participating in School of the air. Until then it’s all fun.

The stations are vast affairs. The first one we visited is called Anthony’s Lagoon. It is about forty minutes flight time from Elliott, in the heart of the Barkly. We saw two people from that station but a nearby station called Walhollow sent across about eight people; so it turned out to be a busy afternoon. I have to record my notes on a word file as our normal software system we use at the clinic, is not available due to software and internet issues. It means I will spend the afternoon of my return transcribing it and copying it into PICUS.

The stations are trim, neat affairs with grassy lawns sporting cane toads desultorily hopping and the occasional King Brown snake slithering around a tree. It pays to use a torch at night as it would not be prudent to mistakenly stand on one, well either actually. Cane toads have recently arrived in the Barkly, travelling down the rivers and lagoons in the wet season. Even sea snakes have been washed here, about five hundred kilometres from the coast in gulf country such is the turbulence and abundance of water, thee can be seen swimming in the huge rivers. The buildings are steel clad, with comfortable interiors and basic but comfortable furniture and bedding. The verandas have chairs to sit and enjoy the evening chill and stretch out the legs. There is a mess hall, with a cooked breakfast at 5:30 am, lunch at noon and dinner at 7 pm. The standard of cooking varies with last nights meal of corn beef and vegetables the stand out. The station staff, sit at the tables, swapping stories about their days. They spend the day moving and managing the cattle, usually on horseback. Horsemanship is a very valued aspect of Barkly Culture.

Tomorrow the Brunett Races and Campdraft will be held about twenty-five kilometres from Brunett Station. Many of the local station staff and locals, will go to see the events and many will participate. Racing is a keen affair, it’s only local horses that can be entered in the events. The festival goes on for three days. There is bush poetry, music but the highlight is the Campdraft competition. Jodie, the receptionist explained what she will be doing when she competes. A fence encloses an area of two hundred square meters. In the square are a dozen steer. The competitor is on a horse, and the aim is to cut out one selected cow, move it into the centre, get it to turn two or three times. Now all this is done using the horse to manoeuvre the bigger animal. Then lead it out through a gate and then back in. The “gate” are two white hats in the enclosure. In real life, on a station, the skills and speed of this sort of activity means the safer movement of stock. The competitor who does it with the most style and speed wins. There is a womens and mens competition but again in the real world of station work, teams of station hands all work together. Some teams of a dozen or more, can be all female. The staff of whichever gender are expected to do the same work. In the evening, the girls are just as dirty and dishevelled from working as the fellows. Frequently, the staff are on camp. These camps can last weeks, working cattle over long distances to fresh bores and feed, while each night is spent sleeping under the stars.

Some of the young people are locals who were born here, some are long term visitors from Europe or the UK. From the dinner table, you can hear German, upper crust English accents and the drawl of NSW rural Strine. Its definitely an eclectic mix. There are some Aborigines but really, very few, and usually born on the station and as they have never left, never having experienced tribal life in a remote community.

The medicine is typical white fella medicine, contraception, smoking, and trauma mostly. There is none of the diabetes and kidney disease rampant in any Aboriginal community.

You may recall the photos I sent of Marlinja. Marlinja consists of a pleasant Aboriginal community, on land that was returned from the vast Newcastle Waters Station in the seventies: the station itself and between the two the ghost town of the original Marlinja. Here we parked the car, and walked through the old buildings. There is the abandoned Jones Hotel, the general store, and the petrol station with its old fashioned bowser. Marlinja was a thriving community, and the shops operating in the the locals lifetime. When there were poorer roads and few vehicles, it took a whole day to get to Elliott which is thirty kilometres away, it made sense to have amenities close by. Now food and supplies are flown in directly to the station. The famous Marrinjah ( Way stock route that enable stock to be moved from WA to Queensland brought huge mobs of drovers into the Jones Hotel for beer, shower and a comfortable bed. This stock route was also called the Death Way, as it went through desert, jungle, crossed lagoons and often flooded rovers, with snakes, crocodiles, all together a challenging journey for men and beasts. There is a very good book written about this which I will try to obtain if not in Tennant Creek, then on Booktopia.

When I look up from my writing, I can look across the wing and see down onto the Barkly, vast mottled and hazy regions of green in the now desiccated lagoons and desperately hugging the few waterholes still remaining. The rest is a brown flat land scarred by the sinuous paths of now dead rivers and the long, straight dirt roads connect bores and stations.

By the way, a bore runner is a person who drives from bore to bore checking they are working. Some times they are diesel mechanics but generally, they are people who love isolation and quiet.

Central Australia trip to Elliot

It’s Monday night and I’m sitting in my camping chair at the Outback Caravan Park, in Tennant Creek. We began our drive yesterday morning, travelling from Alice Springs to Devils Marbles. It’s 398 kilometres of the Stuart Highway. I took us about five hours including a stop at Ti Tree for lunch. A fine sunny day for driving.

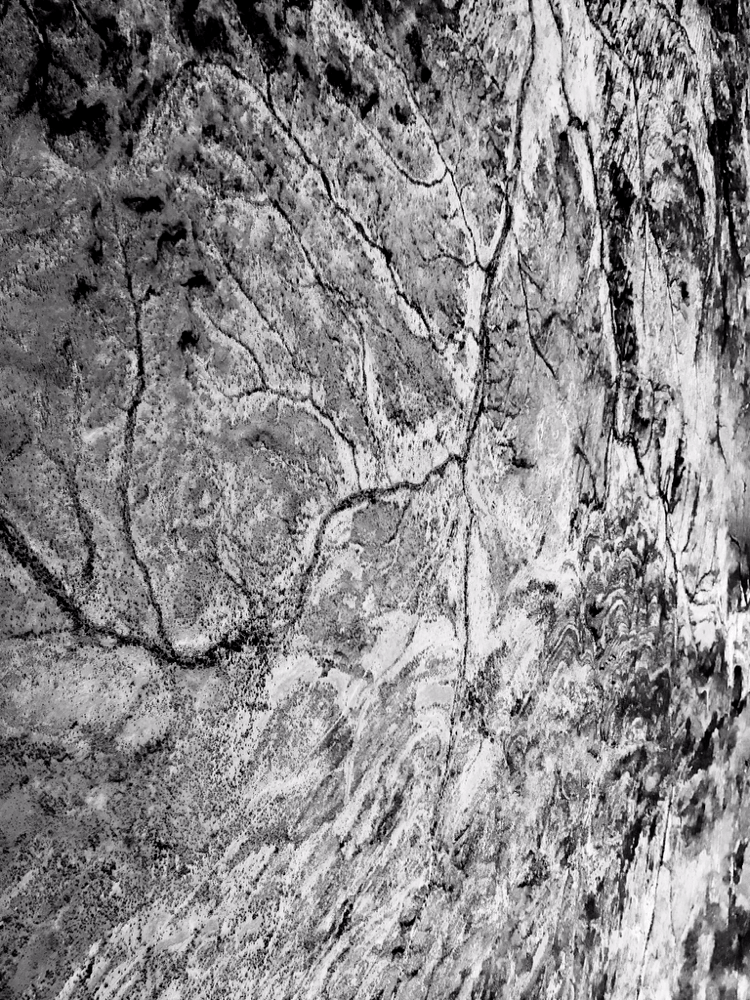

Devils Marbles is one of the highlights of the Stuart Highway. Jennifer and I have visited this park before but it was always a rush, this time we could explore and take photographs at the two best times with no need to scuttle back to work and before it got too dark to drive safely. We walked on the many trails amongst the rock formations. The setting sun sets the rocks red aglow, the grass is backlit as it swirls in the wind, and the gums provide dabs of green and white through the landscape. Devils Marbles are the eroded superficial remains of a much deeper granite massif that arose under an immense layer of more ancient sedimentary rock, sea floor rock, then as the softer surface rock was eroded away the tougher granite remained. But this granite had already been altered, cracked, and split and when it arose into the light of day, these cracks filled with mud and water, splitting the rocks into the weathered Marbles we see today.

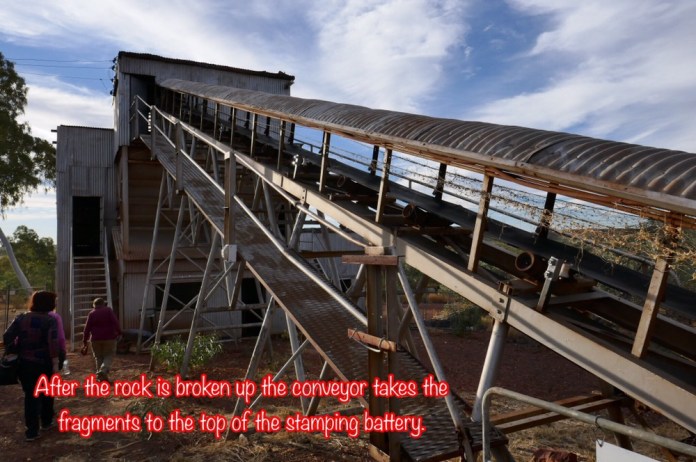

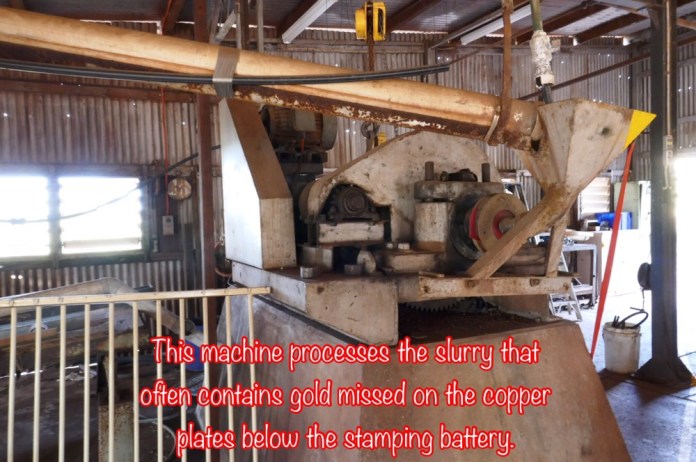

We arrived back at our campsite just as it was becoming dark and cooling down. Overnight it’s very cold so it’s great to be able to rug up in our comfortable camper trailer, under a generous doona. We awoke at seven am, and walked another trail amongst the Marbles and again, were busy taking lots of photographs. We left at 10 am and drove 100 kilometres to Tennant creek. This had very little open on a Monday holiday but the Battery Mine was open. This is a retired mine and processing facility for the gold found in Tennant creek. Beginning in 1926, Tennant creek has been a reliable producer of gold. In all by 1996, 130 tonnes of gold had been recovered. As well as 270,000 tonnes of copper. What makes this area so unique is that unlike Victoria, and most other gold rushes , the gold is in ironstone and not quartz. Quartz is relatively easy to separate from its contained gold, it’s much softer and the gold is often in chunks or nuggets. In Tennant creek, the gold is in fine fragments, too small to even in see most circumstances. Lumps of ironstone, need to be crushed into dust to gather the gold inside it. The ironstone located beneath the water table is generally richer , it’s called magnetite. And you guessed it, it’s strongly magnetic as well. The denser the ironstone, the more magnetic the ironstone then the more gold will be in it. So remote sensing can be used today to locate more gold bearing deposits.

In the early days, mining businesses were small concerns, one or two blokes, both worked a mine in truly appalling conditions. One man would be lowered down a mine shaft in a bucket, using one leg, to push off the mine shaft wall, then at the bottom use a pick to break off fragments of ironstone. The actual shaft went down through mudstone, as no one can go directly through the ironstone deposit. You have to shimmy up to it and chip off the bit in front of you. It was hot and incredibly dusty. The town grew but it was mostly men. The isolation and lack of female company, made life pretty dangerous at times. Was it worth it? For those men who worked the mines, most did little more than pay their way, but some did do well eventually becoming truly big mining companies but overall the capital and size needed to make a go of this sort of mining, ensured it was the big players, the ones who arrived in the 1950’s which made the really big money and still do.

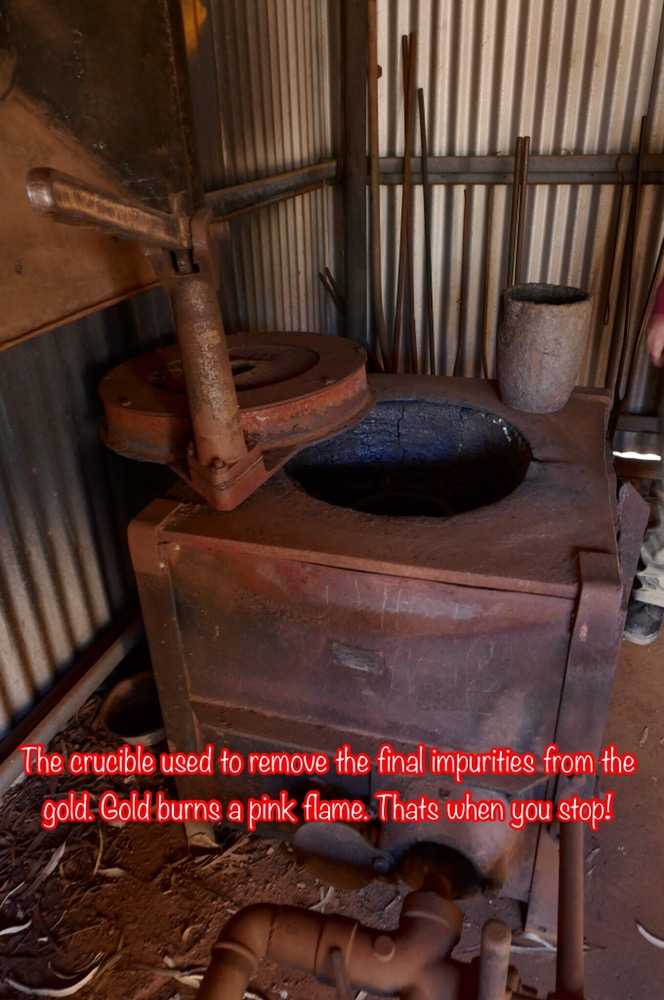

We did two tours. The first tour was through a “mine” built deliberately by Normanby Mines to be used for tourism. They had the expertise to make it as realistic as possible. Along the mine, the guide, showed us examples of mining, form the very early days, to the much more mechanised mining on the 1950s and 1960’s. We were shown the drills, the explosives, the crib room where the men sheltered during blasting, the Beethoven box used by the “powder monkey” to set off the explosives. We saw the mine shaft and the ladder ready and waiting to provide an exit for flooding in the mine. Huge pumps at the base of the mine kept the water out, but as the mine was a kilometre below the water table, a failed pump lead to rapid flooding. The second tour was of the stamping battery. This facility ground up to mined ironstone into a fine dust, you could then use mercury to bind the gold. The amalgam so formed had to be heated in a retort to seperate it from the gold, then the gold had to be heated to fen higher temperatures in a crucible to remove final impurities. A whole years work for a miner in the early days, would produce one or at Most two ingots of gold. An ingot was worth 50,000 dollars, that was a for a year, of 16 hour days, in hot, dusty, noisy and dangerous conditions.

Afterwards, we drove back to our campsite to relax before dinner. It’s getting cold now. I can hear the cars and trucks on the highway, but only faintly. And that will be us too, as we compete our trip to Elliott tomorrow.

Central Australia Road Trip number 4

This week I have spent working at Laramba from Monday morning to departure on Friday morning. It is easily the most friendly place I work, and this trip did not disappoint. I drove up north along the Stuart Highway, to the turn off to Laramba. It’s an eighty kilometre stretch of sand and dirt, and the troopie struggled. The old problem with these otherwise legendarily tough vehicles is the narrower wheel base of the front versus the back wheels, that makes them slidey slippery on sand. Any how, low 4 WD got me out of trouble, albeit being very slow; well at least I kept moving.

The week has gone well, gradually and methodically working through the listed patients. Francis and Isobel are the two Aboriginal workers who take the clinic car, and try and locate them in the community.

On Friday, I was at the final meeting for the week before the drive back to Alice Springs. I’m very glad I took the option to stay longer because of a wonderful dinner with Helen and Brian, at her place and the chance to talk with Robbie Charles. He is arguably the most articulate and clear thinking Aboriginal person I have met. Robbie is the Project Officer for the transition to having a Community committe in each location that will meet regularly, and to meet with clinic staff and the district manager of the health service. There are already committees that meet representatives from public services such as for housing, power and water. Usually the same key people are in most committees as throughout human history!

The community group cannot force the clinic or health service to do anything but will be a regular source of advice for the clinic, as well as giving the communities the opportunity to air grievances or suggest ways of improving health care delivery. It is to be a two way process where clinic managers can point out ways the community can contribute to improving health, such as financing a regular bus to town. It’s quite an exciting prospect and it’s being rolled out by aboriginal people from these actual communities.

Hermannsburg, NT

About 125 kilometres west from Alice Springs, a drive will take you to Hermannsburg Historic precinct. It’s a beautiful trip with the magnificent red sandstone cliffs and hills of the West McDonnell’s to the south and to the north, the rolling hills of the Arrente. The trip only take 90 minutes along a sealed road. There are signs warning of horses and kangaroos but these are much more of a danger at night than in the daytime. For some lengths of Larapinta Drive, stock can wander over the road as well, so it best to be alert day or night!

Hermannsburg is a living community with about 700 people of which over 600 are Aboriginal. We drove past the roads that lead to the houses and the few shops, instead following the signs to the historic precinct. After being there for two hours, enjoying it enormously, we would both strongly recommend a visit if you ever have the opportunity.

Hermannsburg, the name, comes from the city in Germany where the first Lutheran missionaries to this region were trained. The first two arrived in 1877 only a few years after the explorers and the even more recent pastoralists. The Aborigines who lived in this area, now called the Finke by thewhite people, faced an uncertain future. Their land was taken from them because the pastoralists needed it for their stock. Police were pretty hostile too, with many local people shot and killed. Charges never lead to a conviction for a white policeman for doing this sort of thing.

They were lost, starving and extinction was a real possibility.

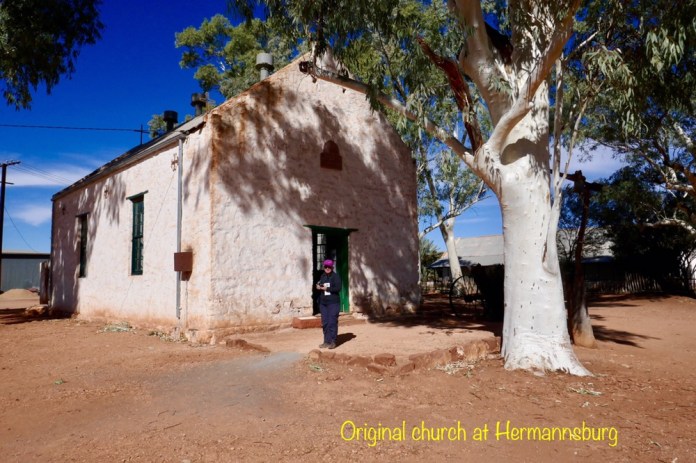

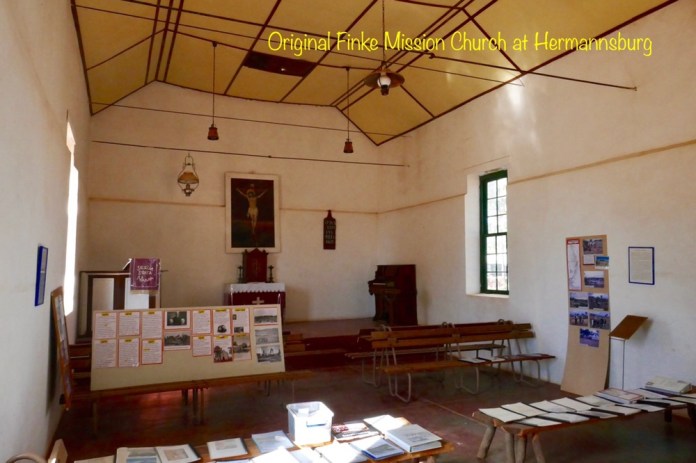

Many missions in Australia, and in colonies all over the world have been rightly criticised for being the soft side of colonialism and as important in destroying local culture as guns and soldiers were. Here I think it was different. The Finke River Mission provided a refuge, food, accommodation, and what medical help they could offer. The difficulties in getting supplies to the mission in its early days were horrendous and expensive. None the less, tradespeople who came as well as the pastors, built the church and out buildings, some of which are still standing.

Notably, Carl Strehlow, the pastor from 1894 to 1922 at the mission, was fluent in Arrente and produced the New Testament in that language. This had never been done before, anywhere in Australia. During his time there, he and his wife survived droughts, financial difficulties and the hostility of many people including government during world war 1.

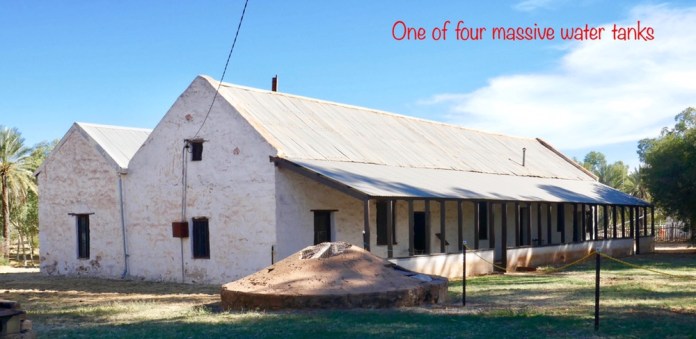

Up until the 1920s, the children suffered terribly in droughts. No food could be grown, particularly vegetables and in one particularly terrible drought, 85% of the children died from scurvy. In those days there was no rail link from the south and no way of getting food to this remote area. Soon after, the mission built what was regarded as impossible, a pipe to a reliable spring that could fill their massive water storage tanks and finally grow vegetables and food all year round.

Trade schools were set up, especially a tannery and leather processing business. The Aboriginals made leather from cattle and kangaroos. They made shoes. The women processed salt to help safely store meat for many months in the dry, hot conditions. It was a viable community until the attitudes to missions changed, and many Aboriginals drifted away to outstations now funded by government and nearer their own lands. The modern pastors and families of the seventies would no longer put up with the deprivations of the early years. The Lutheran church pulled the pin, moving its administration, efforts and funds to Alice Springs.

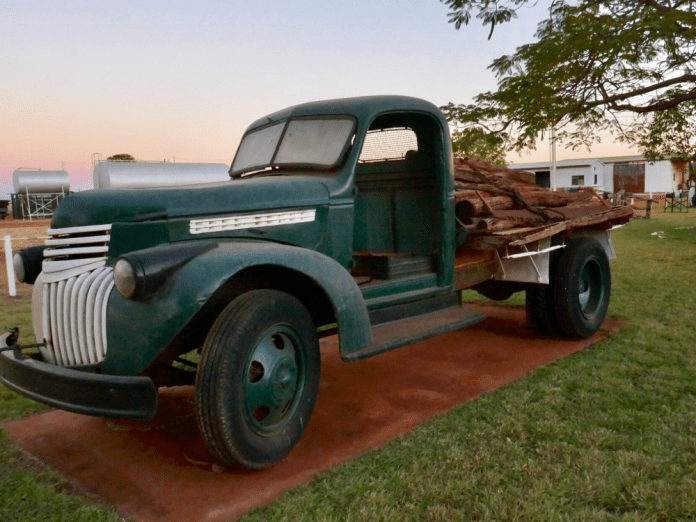

The old buildings still exist. In the middle is the tall white church. Out the front are two river red gums. A steel beam balances between them, and from that beam hangs the church bell. The early pastors had serious doubts about the safety of building a steeple. The walls are thick, cool, and limed white inside and out. The walls are made of limestone blocks that were dug and prepared nearby and moved by cart. Around the church are the Tannery, the manse, the bakery, five massive buried water tanks, accomodation, infirmary and dental office. Behind the buildings are a grove of date palms, a useful food supply in this hot climate. In the buildings are artefacts left over from the working years of the mission. Restoration projects on cars and equipment is slowly happening, including a mechanical, motorised borer.

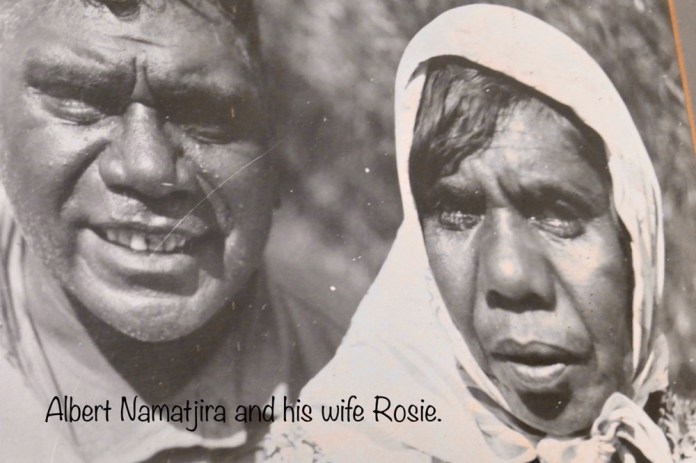

A highlight for our visit, is all the information as well some paintings by Albert Namatjira. He was born near Hermannsburg and spent most of his life nearby. As a young man he had the great good fortune to meet Rex Batterbee. Rex was a water colourist, and a very good one, who had travelled northwards from Melbourne to explore and paint views of the country around Alice Springs. He quickly realised what a great painter Albert could be, and taught him the artistic skills he needed. The student soon overtook the master. In 1936, he had a solo exhibition of his work in Melbourne. He soon became very famous. He produced a tremendous body of outstanding work. However, this fame backfired, as he was given the unique right amongst Aboriginals, to buy alcohol. Under the humbug rule, where you have to supply friends or family with whatever they want if you possibly can, he supplied lots of grog to these people at Alice Springs. Outside town, there was notorious drunkenness and violence due to this preventable situation. When a girl was murdered in the camp, enough was enough, and he was jailed. It truly broke him, and he died a month after his release.

We had some of the local fare at the tea rooms, formerly Carl Strehlow’s home. Strudel of Course! If you look up from the desser, you can see the mulga tree branches still forming the roof supports. We walked through the dining rooms, reading the displays, enjoying Albert Namatjira ‘s paintings, and enjoying the peace and quiet. However, as we stood near the church, we could hear local Aborigines singing enthusiastically as part of a a Saturday church service. There are CDs in the gift shop of their concerts performed both here and overseas. The modern church is much more comfortable, it is also built from local stone but it’s not limestone but sandstone that forms the walls. It’s only just big enough for its congregation.

This mission is a reminder of the courage and resourcefulness of the early pioneers of central Australia, and the religious zeal that inspired the early Lutheran pastors to protect and foster the Aboriginal people. Today, there is a strong Lutheran presence in many communities, but they are mostly Aboriginal pastors. There is no problem at all blending the Christian message with the dreamtime stories. And there never has been. When a pastor became very sick, one of the mission Aboriginals said he would get help from Alice Springs. He left the mission, picked up a handful of grass and laid it in a fork of a tree, and sang a song to the sun, for it not to set until he had completed his trip. He travelled far and fast covering the distance from Hermannsburg to Alice Springs and back in three days. He then removed the grass, placed it back on the earth and thanked the sun. He was a well known Lutheran pastor in his own right.

Central Australia Road trip 2 lake Nash

It is Thursday evening and the working week is drawing to close. I’m lying in bed in the donga. It’s been very cold at night so I’m wearing my thermal top and my black beanie. The wind is howling outside. There are some street lights on the road beside the donga, just beyond the wire mesh fence. It is very quiet for a change, the cold and wind keeping the dogs huddled together on verandahs rather than barking at the moon and stars. In the morning we will go for a walk. We walk along the Sandover Highway, all of four meters wide and made of hard red clay starting to crack and tessellate as the summer wet finally dries out. The plains of spinifex and grass are dead yellow, faded from their rich summer green. Cockatoos and corellas group in masses in the few trees, looking like pallid tropical flowers amongst the leaves and branches till they erupt together into the air, keening and calling.

We walk over the plain, diverting onto dusty, nearly overgrown side roads , it would be too easy to get lost in the maze of intersecting tracks. We carry sticks to threaten the dogs nearer town if they get too cheeky. There is always a beautiful sunrise to the east, it can be vivid pink and red, or a burnt dry orange, lighting up along ripples of clouds. The sky is clear and deep blue, and fades only minimally as the day truly begins and the sun climbs above the horizon.

We walk over the plain, diverting onto dusty, nearly overgrown side roads , it would be too easy to get lost in the maze of intersecting tracks. We carry sticks to threaten the dogs nearer town if they get too cheeky. There is always a beautiful sunrise to the east, it can be vivid pink and red, or a burnt dry orange, lighting up along ripples of clouds. The sky is clear and deep blue, and fades only minimally as the day truly begins and the sun climbs above the horizon.

After breakfast we head over to the clinic. It’s only a short walk. As Jennifer or I make up our coffees, we settle in for the morning meeting with the other staff. The clinic is badly understaffed and there is a too real possibility the nurse manager will have to forgo her leave. The logistics of providing staff to clinics such as Lake Nash are complicated and difficult. The nurses here have enormous responsibility, severe isolation, and really no hobbies they can pursue. Even walking safely can be difficult with the heat and the dog packs. It takes a tough, resourceful woman to do this job. I say woman because I have met only one of two male nurses in my time. One of the staff left to work elsewhere while we were here. Their level of competence and savvy clinical judgement is incredible. These remote nurses are the best.

It’s been a quiet week for us. At least so far because as you all know, things can get pretty dramatic, pretty quickly even on a half morning’s work tomorrow.

While we have been here in Lake Nash, the news on TV has been about a treaty between whites and blacks. No one has mentioned it here. The people here just get on with life. Politics seems a very long way away. The big players who are passionate about these sorts of things don’t come here. People still buy their coke, forget their tablets and miss important appointments. While other people care for their sisters, listen with intelligence and interest as we explain about their health, and proudly drink water rather than sugar riddled beverages. As a doctor, I see and hear the stories of their lives. Of being a stockman. Of riding hell for leather across this arid country till his horse is tripped by a deep crevice and he is tumbled off and the horse rolling over him. Of being a small boy and walking beside his father as he cares for a vast desert market garden used to provide food for personnel in WW2. Just one of many unwritten stories of the indigenous people’s contribution to this country’s war effort. Of the woman who accompanies her sister three days a week to the local dialysis centre, and does all the work setting up and running the hemodialysis. She will do this forever never complaining, never forgetting. This buddy scheme is the norm in remote communities and again it is an unwritten story of self sacrifice and commitment.

My tapestry grows greater and richer with each person I meet and each story I hear.

All of these stories and people, their voices and faces, are painting in my minds eye a vast canvas coloured by their resilience, warmth and vitality, but tinted with some sadness by the seemingly insoluble and ongoing problems these wonderful people face. I don’t think they care much about a treaty. I think they want to survive and enjoy life as much as they can from one day to the next. Unlike white people who struggle to exist in the present, many Aboriginal people, live far more in the now than we do. This is both good and bad. Living in the moment gives a warmth and spontaneity to life and reduces needless worrying but on the downside, it’s hard to take actions which have a pay off in months or years from now such as taking medication daily. The financial insecurity of Centrelink, the costs of food and services, the social commitments of communal life, sorry business, gambling, alcohol, isolation, the lack of much employment and issues around health, all produce a sometimes chaotic situation in many remote indigenous families. So is it really so very surprising that they want to live in the present moment and avoid focusing on a future which is hard to understand, just plain frightening or of pasts overburdened with loss and grief?

There are not the social and support services here in the bush that we all expect in the major towns and cities. So why do they stay here? Simply because they love this land and are a part of it. For all the difficulties of living remotely, this land is as much a part of them as they are of it. The men talk about the heat of summer, the cold winds of winter, and the satisfaction of having worked on the land. So maybe that is what a treaty needs to be about, their authority over this land. There is a medieval story you may know. A knight has offended a mighty witch and she will stay his punishment only if in one year, he can correctly answer her question. The question being ” Above all else what does a woman want?”. He eventually learned there is a simple answer to the question but it was confronting all the same; the right to choose for herself. I believe that the Aboriginal people in these remote communities should be permitted to choose for themselves too, to run their townships their way and to educate their way. I think we do live in interesting times. Could they do a worse job than white government? Now that’s hard to imagine.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

I have written before about the health impact of water in Central Australia but I learned something new. While we have been at Lake Nash, we met the dentist who comes out to this region. He has done this for thirty years. He told us about a problem at Ali Curung. Dental problems are severe with brown discolouration and loss of enamel, but no decay, due to excessive amounts of fluoride in the water they drink. It’s twenty times the amount added to drinking water in the cities. In addition, tea contains fluoride. And the longer it is brewed the more fluoride is leached into the brew. Here the Aboriginal ladies, brew pots of tea all day or have multiple tea bags in one cup. Unfortunately boiling water for drinking deals with bacteria and viruses but concentrates heavy metals and chemicals. No one has measured the intake for the average person in Ali Curung but it would be three or more times the maximal recommended intake at least. Now fluoride in normal amounts strengthens bone and protects teeth but in large amounts both of these beneficial effects are reversed as bones and teeth cannot form properly. Bones in the arms and legs become brittle and break too easily. Teeth never form proper enamel and pit and break even in adolescence. Normal dental repair and fillings won’t work as the scaffold of healthy enamel is not there. And yet barely forty kilometres away, at Murray Downs, their teeth are perfect aside from soft drink induced caries. Their bore pumps water from a different aquifer. This problem with fluoride has been known for decades but it is considered by government to be too expensive to fix. Water would have to be processed by a costly industrial process to remove the industrial quantities of fluoride.

All the water used in Central Australia is from the great artesian basin, the freshwater it contains comes from as far north as New Guinea and eastwards as far distant as the Great Dividing range. It travels over hundreds of years and thousands of kilometres through horizontal cracks in the sedimentary rock of our ancient seabeds into the rocks beneath central Australia. This vast underwater lake is the Artesian Basin. However it’s quality and safety vary enormously. It can be contaminated by pondages of effluent, or by agricultural chemical run off, seeping down from the surface. It will also be contaminated by the minerals in the earth at their location such as fluoride in Ali Curung, or Uranium salts at Laramba. Water quality is assessed by tallying up to forty different biological agents and mineral toxins, and I recall that very few community bores fulfil all the listed criteria for desirable water in remote Australia. The situation will only get worse as all water reserves are diminishing rapidly due to population pressures. Yuendumu is one example of a town with very limited water security, with a rapidly diminishing supply to its bore. The central desert is littered with communities abandoned due to the local bore dying. When communities run out of water, they have to move elsewhere with a duplication required of all their facilities, few as they are.

The assumption of clean, safe, reliable drinking water is currently not the case in many remote communities. Yet the costs and effort needed to address this issue and provide universal ” town quality water” would be enormous, and clearly quite beyond the capacity of the territory government. Yet would it not be possible to provide even one safe supply of drinking water, one tap adjacent to the shop so at least the locals can fill up water for drinking? Use the bore water for washing and cleaning but have a seperate source of imported or processed water for drinking. Solutions don’t always have to be big and industrial and mind-blowingly expensive.